To Draw a Line

2024BRAIDED ESSAY

Other times we would simply count

Count the many satellites orbiting

the Earth seeing the light moving

across the night sky disappearing

arguing over who saw the most

—Charmaine Papertalk Green,

Wanggamanha: Talking: Listening: Nganggurnmanhaa

I often consider the impossibility of the distance between us and the sky. Only a handful of people have traversed the chasm separating Earth and outer space. For the rest of us, the sky is unreachable, unattainable. So instead, I travelled to the desert. To understand the sky, I had to travel deeper into land. I say deeper, because in the desert, land is everywhere; also, we were driving inland, away from the coast and heading towards the centre of the mass of land that is Australia, so it did seem that we were moving deeper into land.

Prior to the trip, I had to attend a safety briefing because our destination was a working site. The safety officer drew on the whiteboard a map of the journey: a straight line across, with two perpendicular lines up; like the letter F mirrored and rotated clockwise. At that moment, it seemed ridiculous that the map was that simple, just three straight lines. Straight lines dominate. They cut up and impose. It is disconcerting to see straight lines on maps because it means someone simply drew a line from point A to B; humans imposing their desire and rule on land. And on that journey, sitting in the passenger seat, I looked ahead and it was, indeed, an unwavering straight road. We made one left turn, at Pindar, and then travelled north, up the longer of the two perpendicular lines of F.

For the past year, I have been working on an artistic research project on the proliferation of space debris, and this field trip was to help me understand its effect on our night sky. We were travelling through the protected radio-quiet region of Murchison, and had no cellular reception. Along our journey, we were instructed, “at the top of every hour”, to push a button on a satellite transponder in the car, sending a ping of our trip progress to the waiting officer at our destination. I imagined a ticker tape, punching out a measurement of our passage. An hour of wheat field; ping. An hour of bush plants; ping. The bush became sparser; ping. Still more red earth; ping.

A satellite engineer recently told me that if the International Space Station were right above us at our zenith, drawing a line from us to the spacecraft, it would be the same distance travelling from Perth to Albany. I checked on Google maps: a four-and-a-half hour drive.

For our four-hour drive, we would have almost reached the space station.

***

There is a series of photographs, published in Nature magazine, of astronomical images in the archive of the Hubble Space Telescope that have been contaminated by passing satellites. The photographs are black-and-white and grainy. In some images are one or two bright stars, their brilliance spilling out of their allocated pixels as radiating spikes of light; the other photographs feature galaxies and nebulae that are, I assume, many light years away. In all of them are bright white lines streaking across the frame—the contamination in question. The lines are in the foreground, drawn over the stars. One line was captured so close to the telescope lens that it appeared as an out-of-focus band, dominating the entire top left corner of the photograph. I wonder about the stars and galaxies obscured by that white band.

These photographs are optical observations produced by the Hubble Space Telescope between 2002 and 2021, filtered through a deep-learning algorithm trained to identify images containing traces of satellite interference. The bodies of satellites and space junk are made of metal that reflect sunlight off their surfaces as they trace their orbital paths around Earth. Some satellites are as bright as the brightest stars in our night sky, and when they pass the field of vision of any observing telescope, they leave a mark across the image. These lines are labelled as ‘contamination’ and ‘interference’. In one conversation, an astronomer used the word ‘annoyance’ to describe the traces left in the wake of passing satellites.

Yet, when I first saw this set of images, I found them to be beautiful. I printed one out and stuck it on my wall.

Since then, I have found and collected more satellite-tainted photographs. A particular favourite is a two-hour long exposure captured by the Baker-Nunn telescope of M3 (a globular star cluster) and comet C/2020 T2. Two bright spots in the centre of the image. Surrounding them is a pattern of intersecting lines, the passages of multiple satellites recorded during the exposure window. The network of lines resembles a web. Two stars caught in the tangle of a luminous web. And I imagine spiders in the sky, spinning and weaving with the metallic threads of satellites and space stations.

***

It was a cloudless, hot afternoon that day out in the bush desert. I stood on the edge of a water-filled crater—human-made, a gold mine abandoned once the pot of gold had emptied. This was our first pit stop. It was not yet summer, the early-October day still well within the spring season. But it was, nonetheless, very warm; made warmer by the absence of clouds and the flat, arid landscape. It was looking to be the perfect weather for stargazing at night, but during the day, we had to bear with the heat. The crater with its water reflecting the blue of the sky was a mesmerising sight, but I was more captivated by the red of the dirt all around us. As we made our way back to the vehicle, I quickly snapped a photo with my phone: a close-up of the red earth.

We were making our way to the Murchison Widefield Array, a radio telescope that is a precursor to the Square Kilometre Array, the largest radio telescope in the world. It operates on the low-band frequency range, listening to the quietest hums of the universe. For the telescope to perceive the soft signals of distant stars, galaxies, pulsars, and black holes, its antennas have to be situated away from any source of noise, specifically radio noise. Radio interferences are emitted from our phones, radio broadcasts, Wi-Fi internet, Bluetooth, and most of the electronic devices that we use. The more noise we create, the further out the telescopes have to be. Back in the car, I switched my phone to aeroplane mode.

We had been driving for a while. The view from the vehicle was unvarying: a wide dirt road, alternating between bumpy and smooth, with more red earth on the sides where low bush plants and skeletal trees grow. We had missed the wildflower season by a couple of weeks. The desert blooms, they told me, are beautiful in August. The only evidence of the blooms that had just passed were the sporadic patches of purple in the bush. For most of the ride, we had to content ourselves with the monotonous view of red and more red—a relentless, hypnotic red. But I liked that. The monotony put distance between us and our destination. It gave me a sense of how remote the telescope is, how far we had to go to get away from the din of it all. Rebecca Solnit writes: “Blue is the colour of longing for the distances you never arrive in.” For this journey, I stared ahead, fixated at the end of the road with its shimmering pool of reflected sky—a desert mirage! An illusion making the red earth dance, a trick of the eye elongating and distorting distances, the red pulling away from us always. In this landscape, red—instead of blue—is the colour of destinations unreached.

***

How to draw a line? A line is a sequence of dots, one following another. This was my first lesson in line drawing, during an art class in primary school. I was nine, and that stayed with me as my favourite definition of a line. In order to practise drawing a line, according to the art teacher, we have to first practise drawing a train of dots.

How should we begin, then? With the first dot.

***

The first satellite to be launched in space was Russia’s Sputnik 1. This was in 1957, and since then, we have launched more than 16,000 objects into space. Sputnik followed by Explorer followed by Vanguard followed by Pioneer; one dot after another.

There are approximately 9,000 operating satellites in orbit now. A catalogue, created by the North American Aerospace Defense Command, tracks a number of space objects orbiting Earth in real-time, including satellites both live and dead, spent rocket stages, space junk and debris, and fragments from past collisions and explosions; there are currently about 35,000 objects being monitored. But that is not all. Our ground-based radars are only able to track objects 10 cm or bigger. It is estimated that there are 1 million objects bigger than 1 cm, and 130 million objects bigger than 1 mm. As of now, space companies and countries have filed to put up hundreds of thousands more satellites over the next few decades. (I look at my wall, at the photographs with the streaks and traces of satellite interference, and speculate what the images would look like then. The warp and weft of the webs grow tighter, denser; the stars and galaxies harder to see in between the weave.)

The data points of all the trackable space objects can be viewed as a three-dimensional map. In this digital map, Earth is a sphere and the satellites are displayed as coloured dots, swarming around it. The map is interactive. Zoom out further, and you see the different orbits with their cluster of satellites; click on an individual dot, and the map renders its orbital path. I clicked on one—SL-16 R/B. Its orbit resembles a basket weave, the dot transforming into a line that intertwines around Earth.

***

I cannot explain this tendency to spin these errant lines into weaves and webs, this impulse to borrow metaphors and imagery to make sense of what are considered acts of pollution and violation. In the Chinese language, the word for sky 天 (tiān) is also the same word for heaven and god; the sky a revered place, home of the gods with gilded palaces. Many cultures have deities associated with the sky and stars. Perhaps that is why it is especially difficult to learn of the violation we have been enacting on our skies. To learn of the ease of doing so. Slots and spectrums being filed for in the tens of thousands, as though these satellites exist only as a number in the system, a virtual entity without a physical mass taking up space.

Instead of gilded castles in the sky, I now imagine palaces in ruins, like the etchings of Piranesi. Everywhere there is rubble, debris, junk, waste, and detritus. I had first learned about the space debris problem through a 2019 New Yorker article. The accompanying image is an illustration of bits of hardware—a nut, bolt, spring, gear, key—adrift in space with Earth in the background. Huh, heaven is now a junkyard.

To inhabit this world now is to know grief. We have constructed sites of contamination in our skies; in our lands, oceans, and forests; in our soil and air; in our lungs, our bodies. I can see a single thread running through these different sites, a thread of violence and destruction, holding them all in the same vein, along the same line.

***

After four hours on the dusty road, we arrived at Boolardy station, our home for the night. It was nearing sunset by the time we pulled up at the homestead. When we got out of the vehicle, I noticed our shadows were much taller here. The sun was angled low near the horizon. There were no buildings behind us, where the sun was, and no buildings in front of us, where our shadows were cast on the flat ground. I lifted one leg up and the elongated shadow followed. I reached my hand up and almost touched the sky. We looked like giants, stretching towards the border where land and sky meet.

***

![]()

A while ago, I watched a video of Starlink satellites travelling across the night sky, a string of bright dots moving across the frame in a straight line. Starlink satellites usually travel as a train composed of individual satellites, and are launched in groups of around 40 satellites. They are visible to the naked eye for one to two days after launch, appearing as a dancing line of beads in the sky as they travel higher up in altitude to their final orbit. In the video, the satellites are brighter than any of the stars, resembling silvery pearls against the black of night—a beaded pearl necklace dragged across the sky.

We often forget that the heart of a pearl is a contaminant. A pearl is formed inside an oyster when an irritant, like a grain of sand, slips in between its shell and mantle. To protect its soft, delicate mantle, the oyster secretes a nacre substance of aragonite and conchiolin to cover and encase the irritant, building layer upon layer. Eventually, an iridescent pearl forms.

There is comfort in being reminded of the sand inside the pearl, to know that an armour can be worn as an exquisite coat, that beauty can be borne out of contamination. In describing the satellite as a pearl, I refer to it as both an object of beauty, and a pollutant.

Once the pearlescent necklaces of Starlink satellites arrive at their destination in low-earth orbit, they are mostly invisible to the naked eye. Up there, however, they become irritants to astronomers, disrupting their observations. In optical astronomy, the interruption takes the form of satellite streaks contaminating precious (and expensive) long-exposures of distant stars and galaxies millions of light years away. Astronomers then have to spend time and effort scrubbing these errant lines out of their observations. In radio astronomy, the irritant—the sand in the mollusc—is less visual but no less tangible. Radio astronomers listen out for the radio signals emitted from the far reaches of the universe. The further out in space and back in time they look, the softer the signals are. A satellite or space junk, clunky chunks of metal that they are, produces long, jarring noises that rip through the delicate notes of their observations.

During my artist residency in Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy, I would join in on the weekly fast radio burst (FRB) research meetings. FRBs are mysterious and transient bursts of high-energy pulses that have been observed at different parts of the sky; no one knows what they are and what causes them, the first pulse only discovered in 2007. At the first meeting, a researcher presented a plot of a fast-burst radio signature. More than half of the graph was rendered unreadable, glitched with bold white lines due to an object traversing the recorded patch of sky. “Probably a passing plane or satellites,” he shrugged. I asked if he could email me that image, and made a mental note to pin it on my wall with the other images.

***

There is an artwork, Le Catalogue, by Yann Le Guennec, which allows anyone to access an online archive of the works he created between 1990 and 1996. Each time a page is accessed, a glitch is produced in the form of an intersecting horizontal and vertical line rendered on the work. The more times the page is viewed, the more lines are generated, corrupting the image in the process. Eventually, the whole artwork will be completely obfuscated by the lattice of lines above it. In this deliberate act of destruction, a new work emerges. The errant lines renew the image.

For the last few months, I have been drawing lines. On the large table in my studio, I place tracing papers over a printed map of the constellations, and on the tracing papers I draw lines. By my side is my computer, with the satellite database displayed on the screen. As I am drawing the lines, I search for space debris—fragments of collisions and explosions—flying overhead in the skies, over my ground location. Every object listed in the satellite database has a Two-Line Element Set (TLE) data attached to it, describing its orbital motion. I input the TLE data into the programme and a line is generated on the screen. This line is the real-time path of the debris object across the sky. Using the constellations as coordinates, I copy the line onto the tracing paper; one hand holding a 2B pencil, one hand supporting the ruler, and in one motion I draw the line over the heavens.

I am not sure what I am trying to achieve with this drawing exercise. I tell others that I am exploring an alternative cartography of our night sky, creating a palimpsest of the stars given to us and the stars we put up. But that feels like an oversimplification. The motion of drawing these straight, ruled lines feels strangely cathartic; but also violent. Perhaps, like roads in the landscape, straight lines do not belong on maps. I look at my maps, and the lines seem to slice and cut. I shudder at the catharsis. The errant lines renew the image?

One more metaphor: the etymological root word err means “wander”, with the word errant meaning “wandering”. In antiquity, the Greek astronomers referred to the planets—objects in the sky that move relative to the fixed stars and constellations—as Astra Planeta, or “wandering stars”.

***

At Boolardy that night, we walked out to the airstrip, away from the lights of the homestead, to look at the stars. As we made our way there, Steven Tingay, an astrophysicist and director of the Murchison Widefield Array Telescope, pointed towards the western horizon. “Can you see a wedge of faint light there?” I could, it was barely perceptible. “That’s the zodiacal light,” he explained. I squealed—how lucky we were.

I had just learned about the zodiacal light the week before, speaking to Natasha Hurley-Walker over lunch one day. She is a radio astronomer at the institute, studying long-period radio transients. The zodiacal light, also known as false dawn or dusk, is a light phenomenon that occurs due to sunlight reflecting and scattering off the space dust orbiting the Sun. In springtime, it can be observed as a hazy triangle of pale light after dusk, hence the name false dusk. Natasha mentioned it because we were talking about how we are creating our own rings of artificial debris and dust around Earth. If that happens, she offered, the orbital belts of satellite debris and dust might appear like the zodiacal light.

That we could see the zodiacal light was a good indicator of how dark it was that night. Though the moon was waning at nearly three-quarter full, it was not to be out until after 10pm. We had a good viewing window of dark, moonless, cloudless sky—the perfect conditions for stargazing.

Standing at the airstrip, we had the full view of the Milky Way in front of us. We traced the outline of the Celestial Emu, its head grazing the horizon where the Southern Cross constellation was; the flightless bird diving headfirst into the ground. For the aboriginal Australians, the emu in the Milky Way—known by the Wajarri Yamaji in this region as Yalibirri—is their most important constellation. Unlike the official IAU constellations, the shape of the emu is defined not by the illuminated stars but the dark patches between the cloudy nebulae of the Milky Way. These are known as dark constellations.

Because dark constellations are formed by the dark dust lanes of the Milky Way, they are especially vulnerable to the effects of light pollution. The increase in skyglow from artificial lighting and satellites is erasing many constellations, including the emu. Duane Hamacher, a cultural astronomer, calls this a “form of cultural genocide”, a severing of the relationship, of the closeness and intimacy, between the indigenous people and their ancestral sky.

But there, miles away from the nearest city, it was dark enough to see the emu in the sky and the zodiacal light. “You do not have to sit outside in the dark,” writes Annie Dillard. “If, however, you want to look at the stars, you will find that darkness is necessary. But the stars themselves neither require nor demand it.” I thought about the distance we had to travel just to sit outside in the dark. I set my phone on a tripod, and took a long exposure shot of the stars.

In that darkness, the sky seemed heavy-laden, pregnant with stars, like a ceiling weighing down on us. The bioregion of Murchison is characterised by low mesas and flat plains, with low shrubby vegetation. With no hills or mountains to indicate distances, we could see where the land ends and sky starts, making the sky and stars feel low and close—attainable, even. To the left of where we stood, at the airstrip, were two parallel lines of white, triangular markers defining the runway for the planes to land and takeoff. Regular in their spacings and converging at the horizon, they seem to suggest a finite, fathomable, almost reachable distance to the sky.

Later that night, in bed, I took a closer look at the photograph I had taken of the night sky. I noticed I caught two faint meteor streaks. I searched more: no satellites.

***

![]()

![]()

Lately I have been lurking on astrophotography forums, and one question that often appears is: meteor or satellite? In long-exposure photographs of the night sky, the path of a passing satellite can resemble a meteor streak to an undiscerning eye. In the same way, bright satellites are frequently mistaken for stars. This brings to mind a song by Billy Bragg that goes: “I saw two shooting stars last night / I wished on them but they were only satellites / Is it wrong to wish on space hardware”.

It is a captivating idea, to think of space hardware as wish carriers. To imbue them with a spiritual, other-worldly purpose loftier than its mechanical functions of meteorological observation, or internet coverage, or telecommunication, or military reconnaissance. That a satellite can be more than just equipment or infrastructure. That they can occupy the same brilliance of stars. And that our mythological sky is expansive enough to encompass these deviant, wayward objects in its pantheon of stories.

It was on this premise (this hope?) on which I started this research work as an artist. When I realised that we have been filling up the heavens with bits of metal and junk, and that if we continue to do so, things would grow out of control, and how much control we do not have over this problem. Maybe, like our bivalve friends, I needed a defence mechanism against the grief and hurt of learning, again and again, about the incorrigible destruction we have enacted on our environments. A way to make sense of the profane within the sanctity of our skies. An attempt to reclaim part of the narrative.

I have to be careful though, to always be able to recognise the grain of sand at the heart of it.

***

A meteor is a line. It is the visible passage of a meteoroid—an extraterrestrial body of rock and metal—violently burning up as it enters Earth’s atmosphere. To the lucky stargazer, it appears as a streak or line in the sky, its brightness depending on how large the object is. The bigger the object, the more mass there is to burn, the brighter it appears.

If a satellite or space debris falls back into Earth, it will also burn up in the atmosphere and appear like a meteor. It is similar, but not the same.

“The telltale difference is the speed.” I am talking to Ellie Sansom, a planetary scientist who is an expert on meteors. In her work, she studies the entire passage of the meteor—its journey from meteoroid to meteorite. Because of the similarities, she also investigates the re-entries of satellite and space debris. A meteoroid travels from outer space, sometimes from outside the solar system, so it arrives fast and burns up fiercely; it is quick, blink and you will miss it. Satellites and space debris travel from orbits gravitationally bound to Earth, so they arrive slowly; their streaks, though also dazzling, seem languid in comparison.

Ellie is the lead researcher of the Desert Fireball Network, an interdisciplinary group studying meteors and their resulting meteorites. They have installed remote cameras around Australia that are scanning for fireballs in the night sky. Fireballs, also known as bolides, are meteors that are exceptionally bright—as bright or brighter than magnitude -4, the brightness of Venus. Meteors of this brilliance are usually the spectacular display of large meteoroids burning as they enter headlong into the atmosphere. Large enough, the object will survive the entry and fall onto the ground to become meteorites. Researchers from the Desert Fireball Network will then search the field and recover the meteorite.

Each meteor streak, she explains, contains information that can reveal where the object came from—the meteoroid—and where it landed—the meteorite. By analysing the tail end of the line, they can determine the orbital path of the object and trace its origin in outer space. By analysing the front section of the line, they can chart the trajectory of its fall to the ground, allowing them to pinpoint a search area, known as the strewn field, to retrieve the extraterrestrial rock. A burst of light, and then it is gone. Yet, if they manage to photograph this line, it will contain distances that span from outer space to Earth. Distances compressed. Eventually, it might end up in the palm of the person who finds it.

Later, I will scroll through, on the Desert Fireball Network website, the repository of meteorites they have recovered. Images of alien rocks. The repository also catalogues the photographs of the corresponding meteor. I notice that for most, the streak captured is a series of dots.

***

At Boolardy homestead the morning after, we had a quick breakfast and made our way to the telescope. We drove into the site, demarcated loosely by an open gate and a sign that reads “CSIRO Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory”. Above that is the Wajarri-Yamaji name for the place, Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara, which means “sharing sky and stars”; a reminder of the generosity of the Wajarri people, the traditional owners and custodians of the site, to cohabit the same plot of land and parcel of sky.

The root of the word telescope is from Ancient Greek, with τῆλε tele meaning ‘far’ and σκοπεῖν skopein meaning ‘to look or see’. The name for the Murchison telescope in the Wajarri language is Gurlgamarnu, meaning “the ear that listens to the sky”.

I prefer the Wajarri name. In describing the instrument as an ear, as a sensory organ, it creates an intimate and visceral connection between my body and the sky. And also because there is an absence of any allusion to far distances. For the Wajarri people, the sky is not that far away.

***

![]()

![]()

![]()

Another lesson in line drawing, this time in architecture school. During our first year, we had to learn how to draw freehand lines. One advice was: to draw controlled straight lines, start your line at the bottom then draw upwards—down to up.

On 11 January 2007, China conducted an anti-satellite missile test, launching a kinetic kill vehicle from a launch site in Xichang that destroyed Fengyun-1C, a Chinese weather satellite. It is the largest debris-generating event ever, creating more than 3,000 trackable fragments. The satellite catalogue grew larger. In 2008, the US conducted its own missile test, destroying the satellite USA-193; in 2019, India destroyed Microsat-R; in 2021, Russia destroyed Kosmos-1408. All their missiles, controlled and precise, tracing trajectories from the earth to sky, down to up. All deliberate acts of destruction. And for no other reason other than a show of power.

Lines drawn to destroy. Lines drawn to contaminate, to corrupt.

So I draw my own lines.

I draw these lines as an act of renewal and making, to resist this narrative of destruction imposed on us by the few in charge—the few launching both the satellites, and the missiles that destroy them. The lines I draw are straight lines, human-made. But remember, we have constructed threads and nets and weaves out of lines, and have made these things beautiful. If I could, I would learn how to draw lines like Agnes Martin. As writer Nancy Princenthal, in her biography of the artist, describes one of her works, White Flower: “From a distance, the effect is of diffuse, atmospheric presence. The pencilled net gives the white field at its centre the slightest degree of play. The whole is chaste, pure; it has a devotional feel, and the sense of an ordering: a book of hours, a map of a perfectly ordered world, each island in its place.”

With that in mind, I draw my lines in pencil, and keep my grip loose.

***

One last weave: in an African sky story, the Sun was a man and when he raised his arms, rays of bright light shone from his armpits, a source of light for the world. Alas he grew old, and in his old age, he raised his arms less and the world grew dark. The children of the first bushmen banded together and tossed the old man into the sky, immortalising him as the Sun to give light to the world once more. At night, when it is cold, he covers himself with a blanket. The blanket is old and tattered and the light that escapes through the weaves and holes are the stars in our night sky.

***

Driving past the sign, we entered the land demarcated for the observatory. At first, we did not see the telescope. All around were miles of desert land and low bush flora, with a few dongas—container buildings—scattered about. We drove past a large mesa, sacred to the Wajarri people, and where only men are allowed. Then, from within the landscape, we saw our first glimpses of the telescope: the glints of aluminium in the distance, reflecting the sunlight. It reminded me of the metallic ribbons winegrowers tie on their vines to scare birds away.

It was only when we were up close that we saw the telescope, or rather, the antennas that make up the telescope. Spider-like antennas, clustered together in square tiles, nestled amongst the bush trees and plants; each antenna standing at half-a-metre tall. The telescope is an array telescope so, unlike a parabolic dish telescope, it is composed of many small antennas. The antennas sat low on the land by clinging onto sheets of metal net laid on the ground. Nothing dug, nothing pierced, they just sat. Wild grass grew in between them.

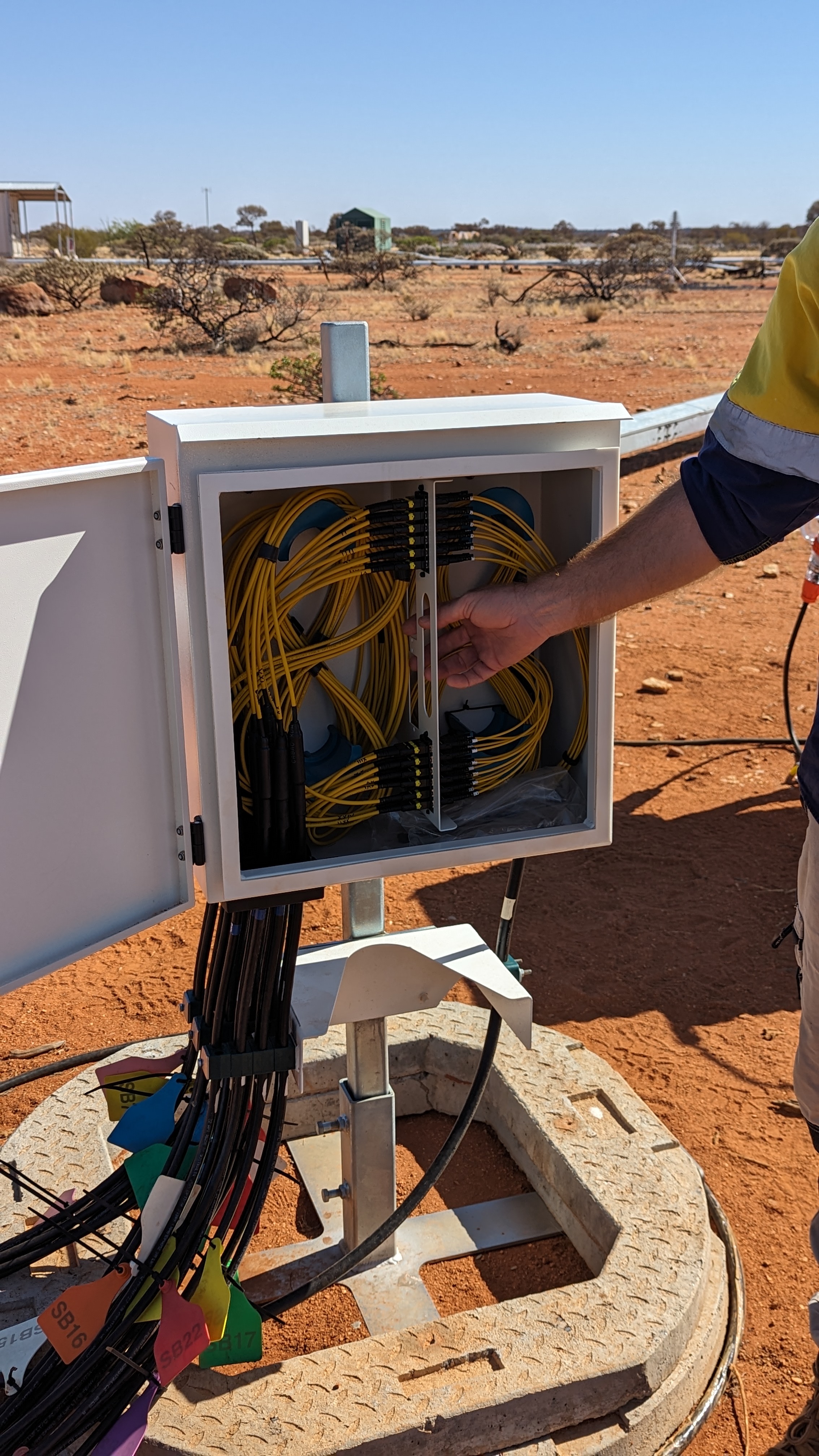

There were black cables, snaked all around the ground, that connected the antennas to each other. They showed me how the cables then connected to thicker cables that connected to the correlators, housed somewhere else on site. Then more cables that connected to the supercomputer back in Perth; the cables tracing the same route we took to get here, and more. I wondered about how some people are suggesting, because of the satellite interference, to put out telescopes on the far side of the moon—and how long of a cable we would need for that. I could not fathom that, not because of the distance to the moon, but rather at the absurdity of it all.

So instead, I took a photograph of the wild grass growing between the antennas. Then, by one of the antennas, I spot a bush of wildflowers, with small, delicate white flowers in full bloom. One of the last to leave, resisting the warmth of the incoming summer.

***

I would like to thank Dr Steven Tingay and Aoife Stapleton from CIRA for organising this trip, and together with Andrew McPhail for showing me around the site. The Wajarri-Yamaji people are the traditional owners of the land and native title holders of the site. I am grateful to Dr Charmaine Papertalk Green and Roni Kerley from Yamaji Art Centre for sharing their knowledge of the land and sky with me.

CREDITS

Field trip organised by Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy (CIRA) Essay developed during the Writing the Braided Essay by Margo Steines

Field trip organised by Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy (CIRA) Essay developed during the Writing the Braided Essay by Margo Steines

EXHIBITIONS

Lucy in the Sky with Debris

Objectifs Centre, Singapore

2024.04.04—2024.04.28

Lucy in the Sky with Debris

Objectifs Centre, Singapore

2024.04.04—2024.04.28